LAND_501 Landscape Architecture Design III: ‘Confluences II: St. Louis and Its Hinterlands’

Micah Stanek, Lecturer

“[C]ontexts imply other contexts, so that each context implies a global network of contexts.”

—Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, (2011, p. 187).

The Gateway Arch commemorates St. Louis’ role as a launching site for the settlement of the American West. For many, it no longer evokes Manifest Destiny but conjures modern architectural ideals and 20th-century engineering feats. The 21st-century redesign of the Gateway Arch National Park reconnected city to park, drawing the indeterminate environment into the design. In this way, the St. Louis riverfront has long been a testing ground for architecture and landscape that represents U.S. history and aspirations.

While the Gateway Mall also points to Westward Expansion, the City Beautiful movement drove the removal of the historic urban core in favor of constructing the string of parks. Ideas of aesthetic clarity, open space, and civic monumentality lay the groundwork; however, block by block, designers and stakeholders shaped and reshaped the open space over time. The Mall recently underwent multiple redesigns, and its character seems to be shifting away from openness toward intensive greening and increased biodiversity. Again, landscapes represent history and aspirations.

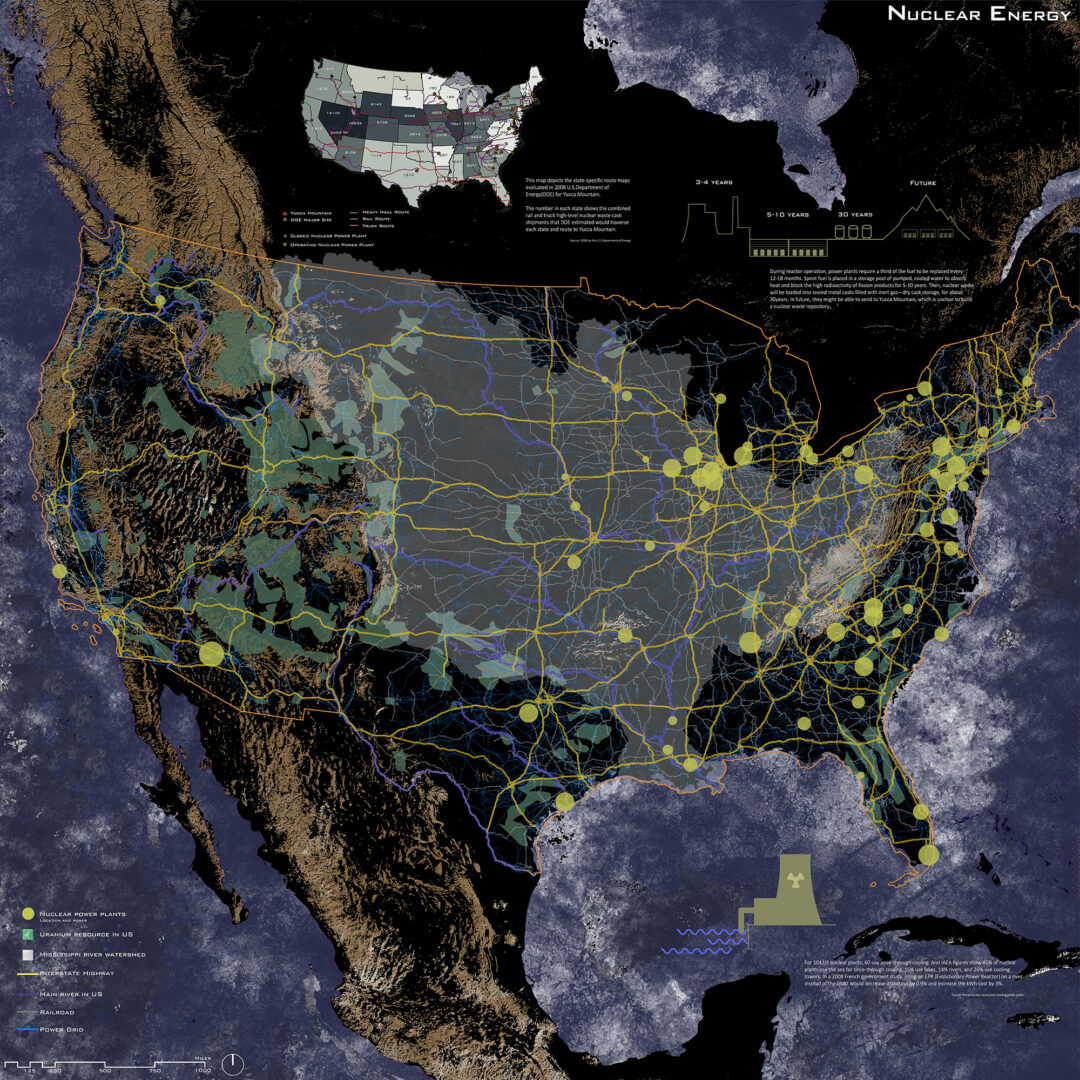

Students in this studio traced infrastructural lines from downtown St. Louis to the hinterland and back. What if the monumental axis extended through the Danforth campus at Washington University? Would it continue up the Missouri River or create a straight section across the Continental Divide and down to the Pacific Ocean? How many crude oil and natural gas pipelines would it cross? How many coal mines?

Traveling to Montana and Wyoming, they sought to understand what connects St. Louis with the American West. They made drawings to visualize how infrastructure overlaps with ecology and how economy and politics impact landscapes. Students also looked downstream to understand the whole watershed context, as well as worldwide to try to disentangle our globalized network of resources and environments. Their drawings told an informed story about how St. Louis and the American West developed, how U.S. infrastructure is changing, and what St. Louis might stand for in the future.

“Landscape architects are…in everything they do, contributing to the political landscapes that all things dwell within.”

—Rod Barnett, “Designing Indian Country” (Places, October 2016)

Returning to the Gateway Mall and the Gateway Arch National Park, students grounded their research through the design of a dialectical landscape—one that fosters the exchange of ideas and invites opposing forces. Large maps and valley sections were employed for understanding our continental context. Experimental drawings and models conflated the site with the hinterland, serving as generative tools. The landscapes and questions in this studio were monumental, so each student studied one infrastructure and each design project took one clear position. Final projects sought to visualize our history, especially the 20th-century infrastructure on which we depend, using design to communicate changing priorities for the 21st century.

Tianhao Xiang

Tianhao Xiang

Tianhao Xiang

Tianhao Xiang

Tianhao Xiang

Danni Hu

Danni Hu

Danni Hu

Danni Hu