URB_711 Elements of Urban Design Studio: ‘Impossible STL’

L. Irene Compadre, Lecturer & Linda C. Samuels, Associate Professor

“We’re on a mission…to save meat. And Earth.”

“If everyone who ate an Impossible Burger in 2018 chose it explicitly over a burger made from cows, we would have collectively spared greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to 250 million driving miles in a typical US car, a land area nearly the size of San Francisco and enough water to hydrate 3 million people for a year.”

—Impossible Foods

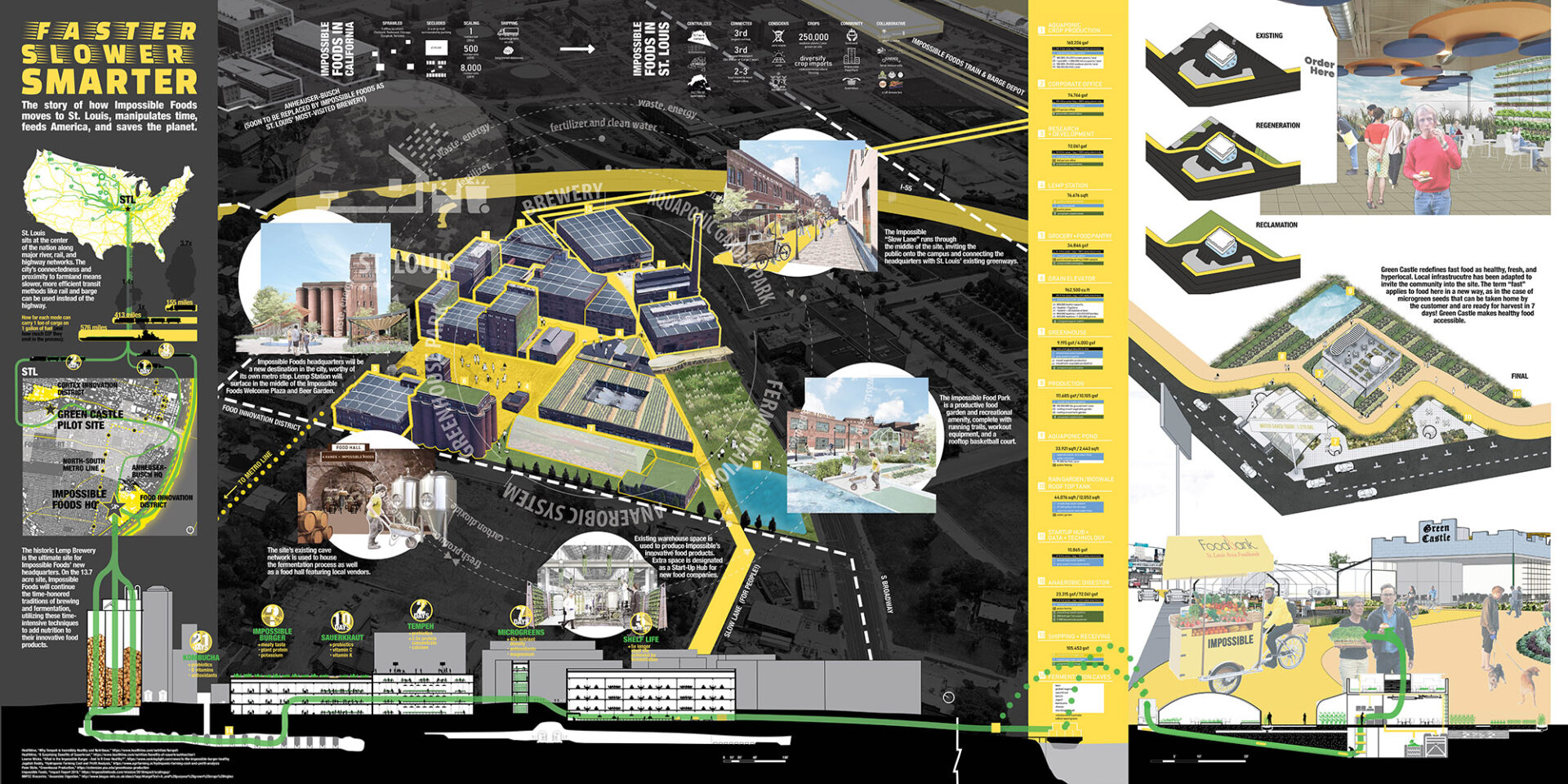

On April 1, 2019—at the risk of being seen as a flame-broiled April Fools’ joke—Burger King launched a test run of the all-plant based Impossible Whopper at 59 locations across St. Louis. Why St. Louis (and not a more stereotypical, vegetarian-friendly city like San Francisco or Los Angeles) was selected as the pilot city is up for speculation. Is St. Louis a sleeper city of environmentalists or a convenient crossroads in the food supply chain? If true, this is an opportunity to rebrand St. Louis as a laboratory for creative thinking around sustainability, particularly symbiotic relationships between health, food, resource use, and innovation. Understanding the many ways to intervene in the currently inefficient and destructive systems of food production could create more advanced and holistic solutions.

This interdisciplinary, systems-based urban design studio emphasized the interconnectivity of macro- to micro-level health, food, resource, and innovation systems, and opportunities for their spatial, social, and environmental design. Hybridizing strategies from landscape architecture, architecture, and urban design, students utilized the tenets of infrastructural urbanism to develop next-generation, integrated design solutions that explored sustainable, innovative, and creative proposals for strategic interventions in multi-scalar systems.

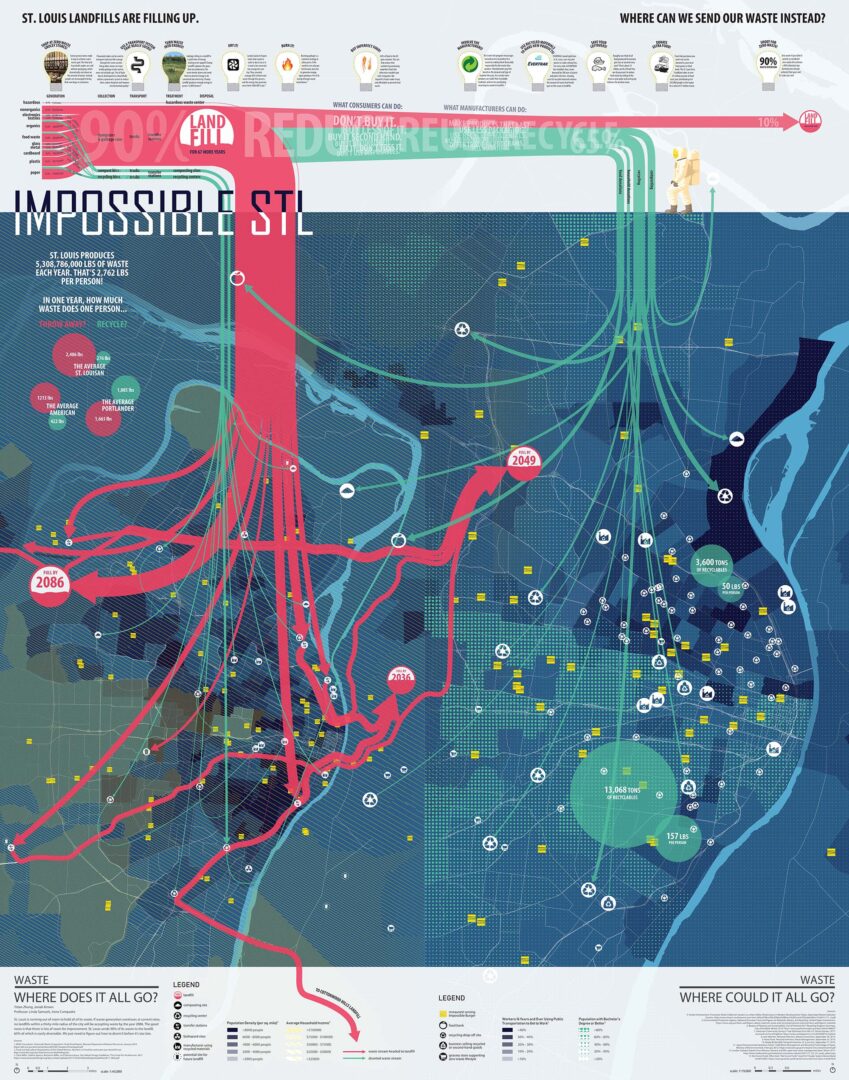

Beginning with Impossible Food’s claims that its burger needs “approximately 75% less water and 95% less land, and generates about 87% lower greenhouse gas emissions than a conventional burger from cows,” students mapped the systems and their relationships that relate to food, including water, waste, energy, agriculture, mobility, land use, access, information, power, hydrology, and ecology. The discrepancies, disruptions, and demands between current patterns and those necessary for projecting a more sustainable future were also mapped. The Impossible Foods company itself was part of the analysis.

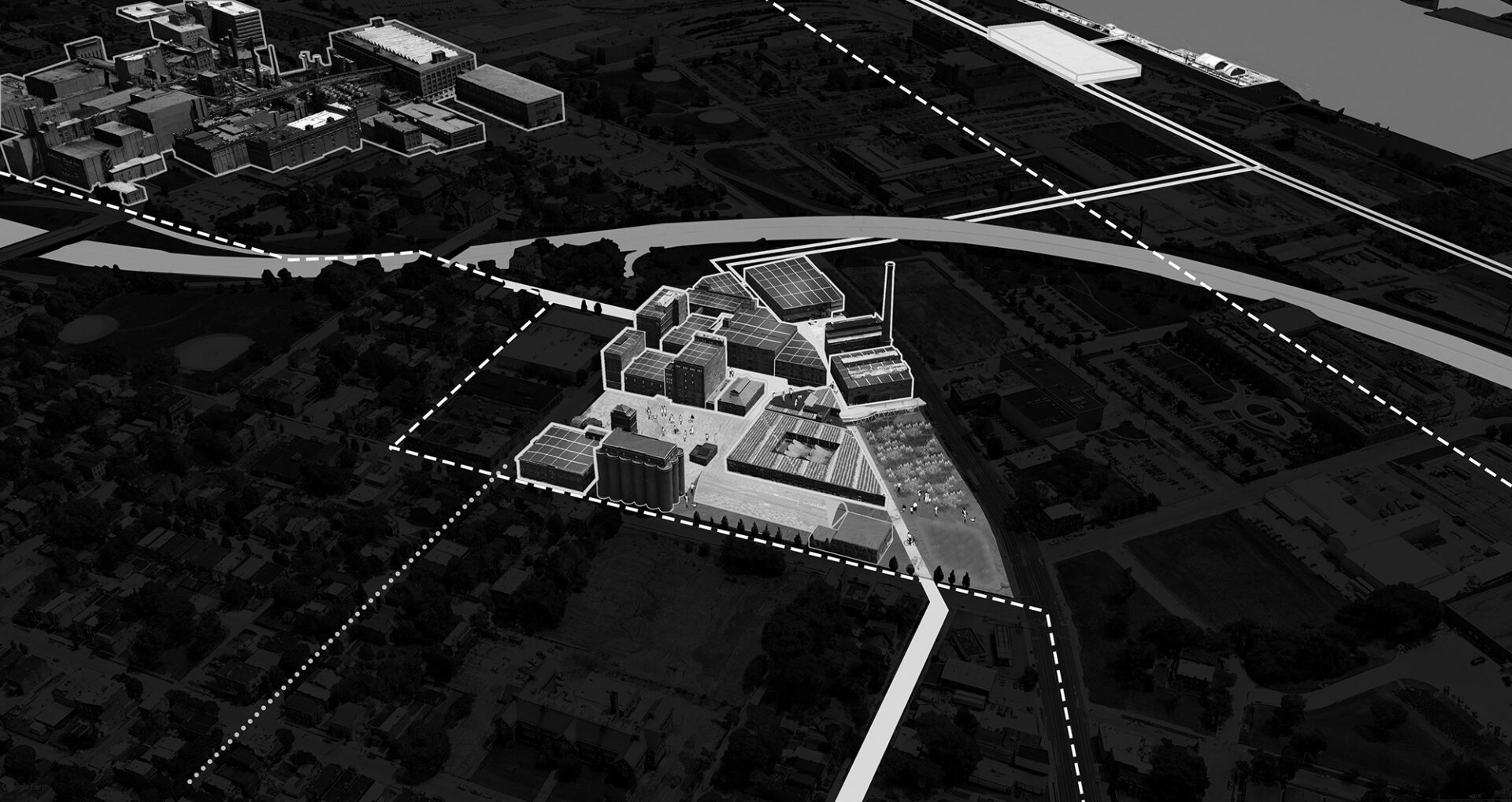

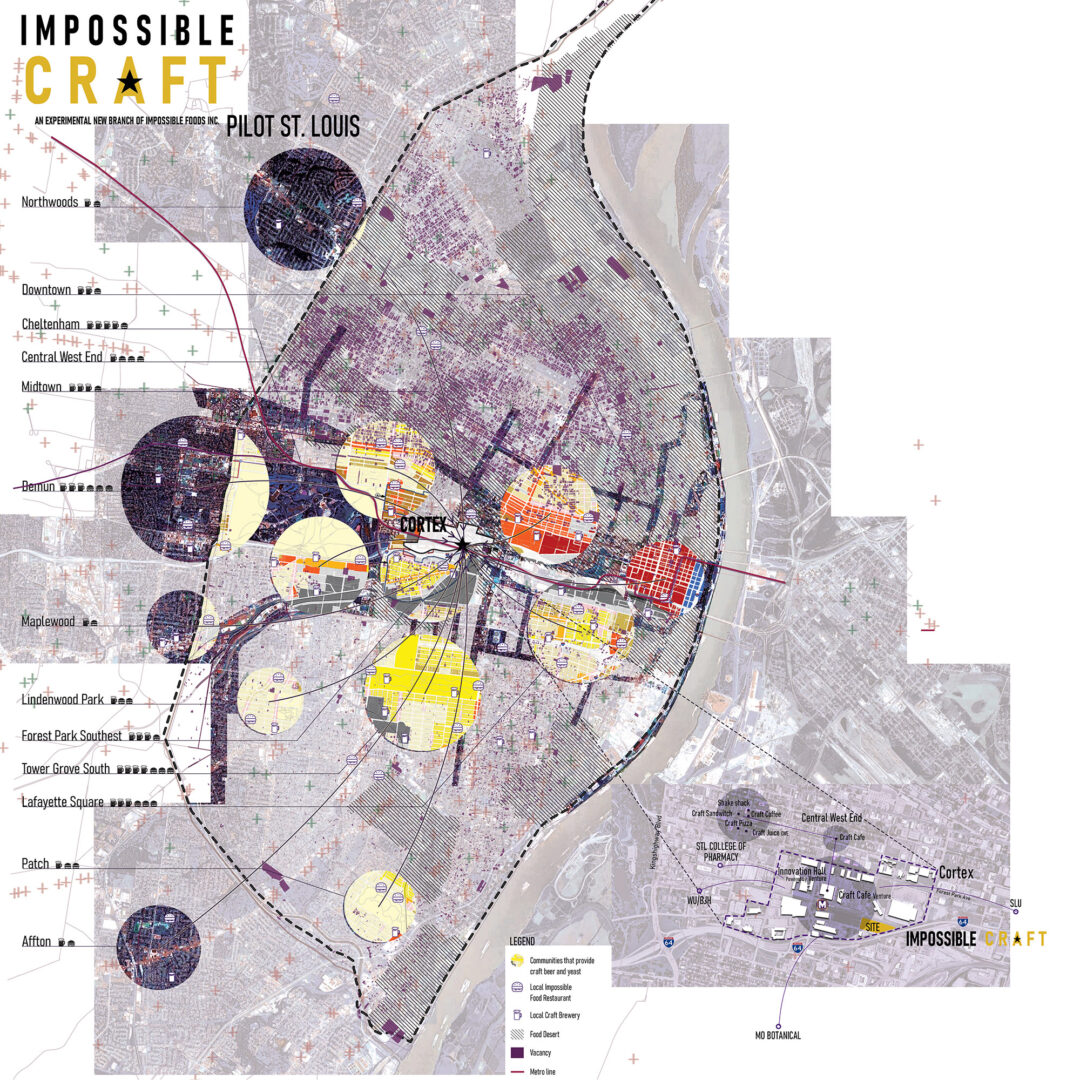

A quick, intense design charrette on a local macro/micro condition followed to help narrow the scope to select sites across the St. Louis area. Final projects took two forms: a centralized catalytic proposition related to the Impossible Foods company relocating a research, manufacturing, or distribution branch in the city of St. Louis, or a decentralized proposition where a network of individual fast-food restaurants, by virtue of their relationships to the Impossible Foods company, act as micro-nuclei of change. Neither strategy was intended to focus on individual sites, blocks, or districts, but on the redesign of overlapping and interdependent systems at multiple scales.

This studio’s ultimate focus was to imagine St. Louis through the perspective of infrastructural optimism—projecting an [Im]possible future that confronts the social challenges of health, access, vacancy, and environmental issues through a narrative of innovation and opportunity. Students took a position, interrogated the facts, and proposed designs to tackle wicked and complex problems while testing spatial strategies to save the planet.

Brown, Mueller, Tao, Liu

Sebastian Jin & Wenjie Yan

Josiah Brown & Yitian Zhang

Brown, Liu, Mueller, Tao

Brown, Liu, Mueller, Tao

Brown, Liu, Mueller, Tao

Jin, Lu, Qu

Jin, Lu, Qu

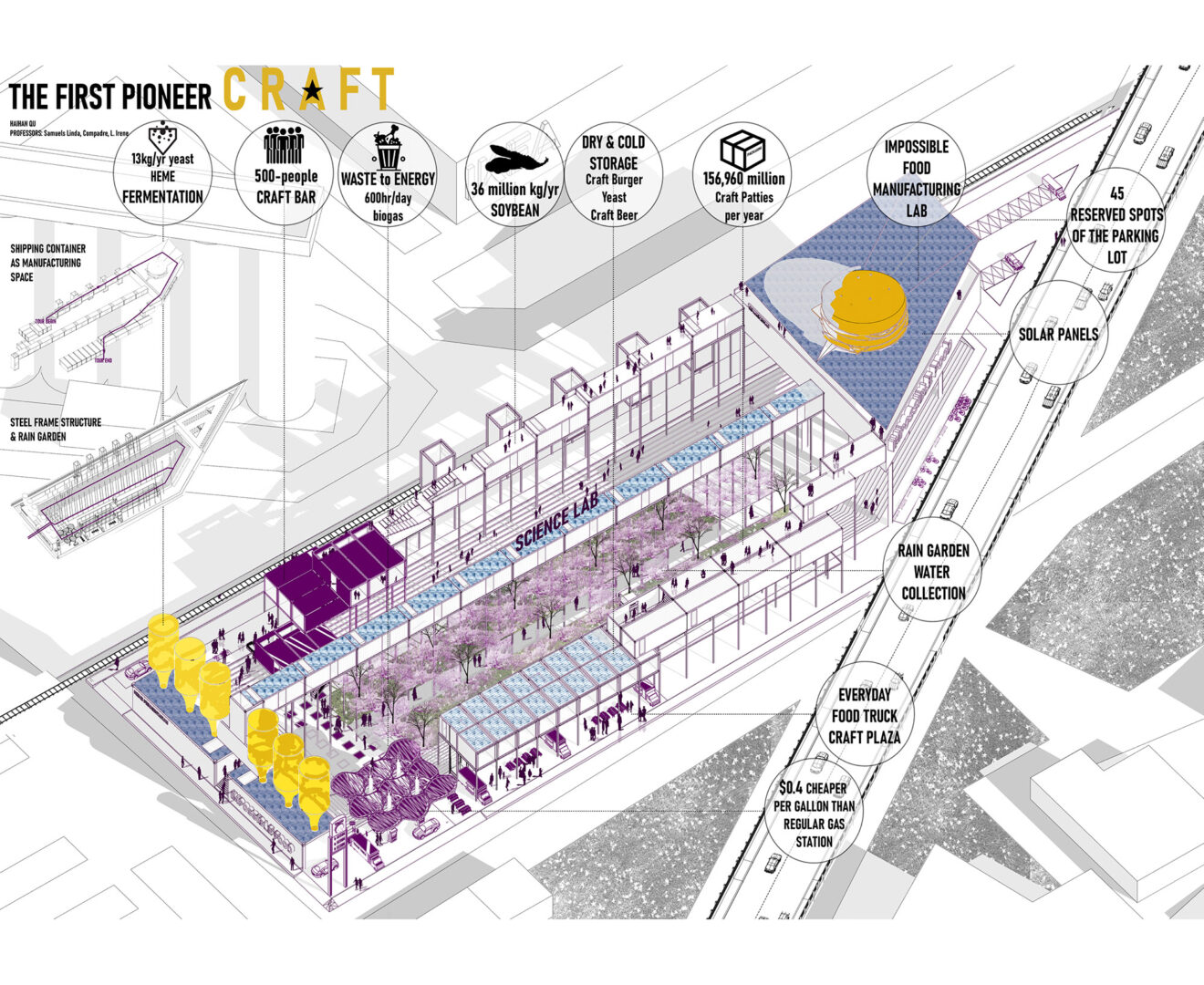

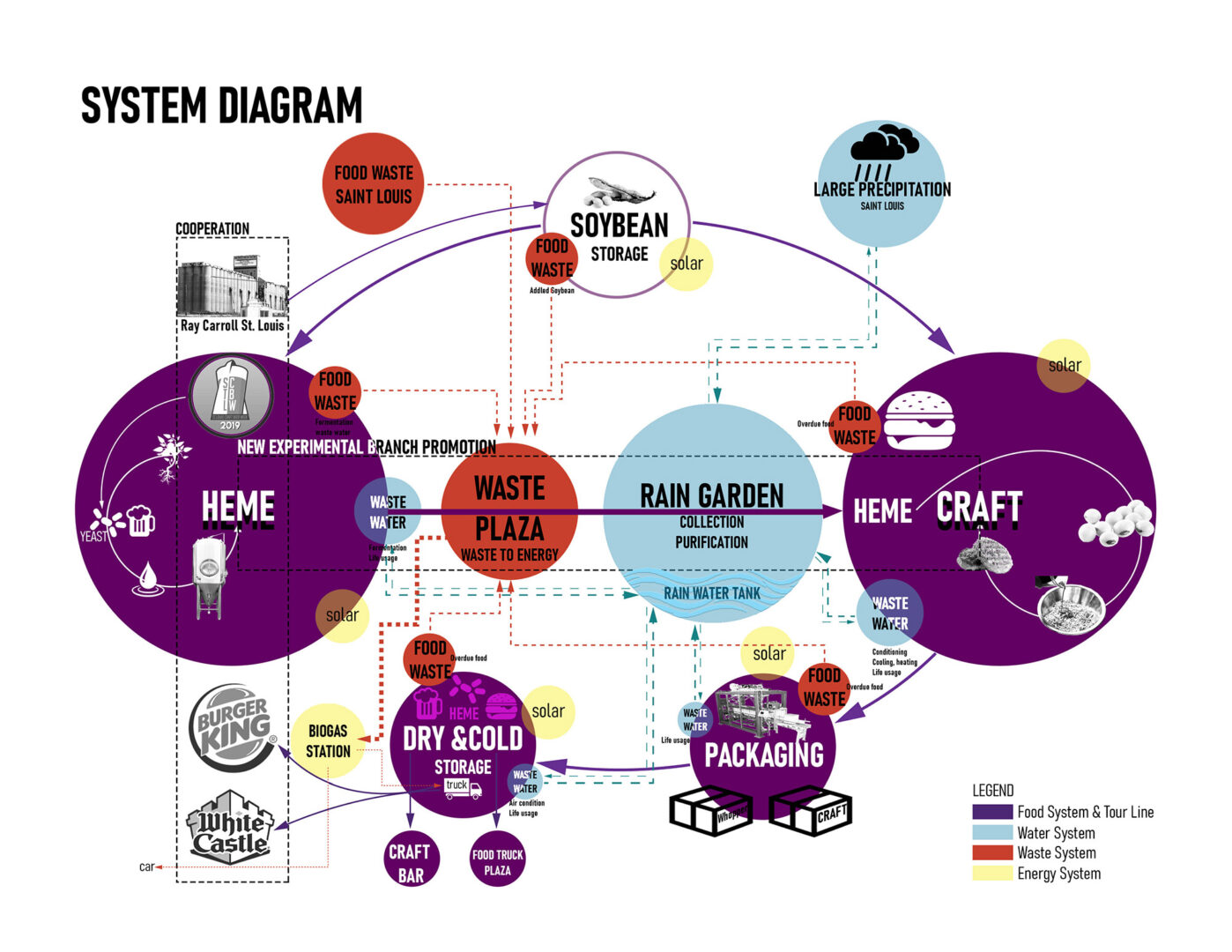

Haihan Qu

Haihan Qu