LAND_502 Landscape Architecture Design IV: ‘From the Bird’s Point to the Bird’s Foot’

Derek Hoeferlin, Associate Professor

“Nature, in this place, had become an enemy of the state…. You’ve heard of Murphy—“What can happen will happen”? This is where Murphy lives…. Man against nature…. There’s no place in the U.S. where there are so many competing interests relating to one water resource…. Old River Control at once became, and has since remained, the civil-works project of highest national priority for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers…. They’re scared as hell. They don’t know what’s going to happen. This is planned chaos. The more planning they do, the more chaotic it is…. The whole deltaic plane, a superhimalaya upside down…. The levees were like cancer, because they had to keep growing while they sank into the swamp.”

John McPhee, “Atchafalaya” (New Yorker, February 23, 1987)

This studio began with research, critique, and speculation about what landscape architecture’s role can be within one of the most powerfully engineered and constructed sites in the U.S.—the Old River Control Complex (ORCC). Located at the juncture of the Atchafalaya, Mississippi, and Red rivers in Louisiana, the ORCC is publicly known to few. Yet it is potentially one of the most—if not arguably the most—important infrastructural acts of control, and by extension American hubris, in the entire Mississippi River Basin. Banal as it is in form, its unequivocal mission is clear and present: absolute control of the Mississippi’s course. If not for the ORCC, everything southeast of it, including Baton Rouge and New Orleans, would not have reason to exist. To put it another way, the OECC mandates and switches the flow of the Mississippi River via regulated percentages and muscular engineering so it continues toward these cities and surrounding economies, instead of due south along the steeper gradient of the Atchafalaya River, where the Mississippi “naturally” wants to flow.

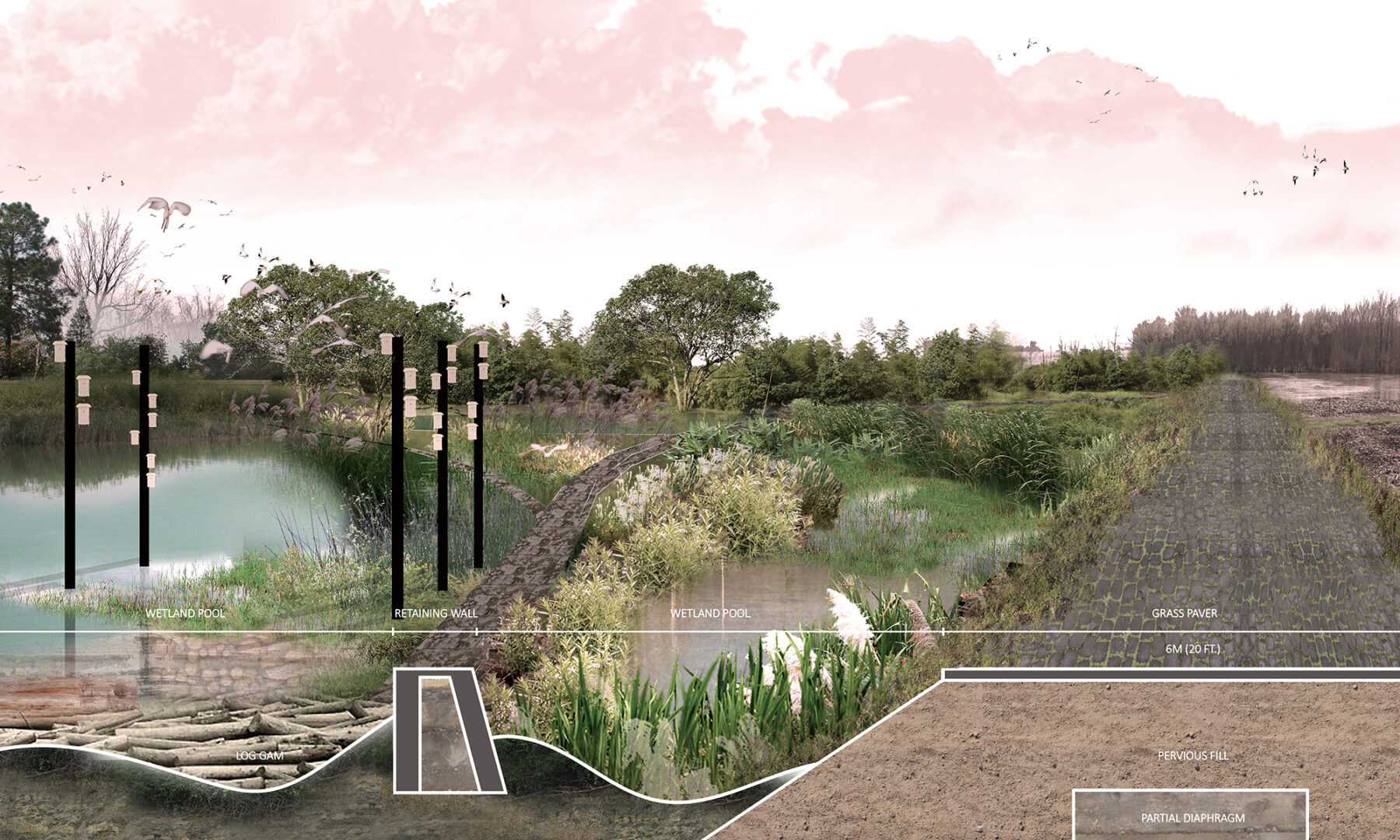

For the first weeks of the semester, students spatially translated John McPhee’s seminal essay “Atchafalaya” (a beautiful yet cautionary tale about the ORCC), into iterative physical models and drawings to formulate abstracted landscape concepts. The translations were both systems-based and physically grounded in their explorations. For the remainder of the semester, using McPhee’s text and their translations as conceptual referents, each student proposed a new landscape toolkit for multiple sites consisting of contextual, programmatic, infrastructural, and ecological control (or non-control), across the entire Lower Mississippi River Basin. Finally, students focused on interventions that centered on one of the toolkit sites, addressing themes of ecology, hydrology, pollution, and species. As a collective vision, the studio proposes the future of the basin as a productive, powerful, water-rich landscape.

To better frame their understanding of the region, students took a road trip through the Lower Mississippi River Basin “From the Bird’s Point to the Bird’s Foot,” visiting sites of control such as the New Madrid Floodway, the Old River Control Complex, and the Morganza and Bonnet Carré spillways. From Cairo, Illinois to New Orleans, Louisiana, students scrutinized these infrastructurally hinterland-based sites in relation to the communities and urbanisms they serve.

Danni Hu

Danni Hu

Danni Hu

Danni Hu

Xue Ying

Xue Ying