LAND_501 Landscape Architecture Design III – Core Studio: ‘Confluences: Fort Defiance and Its Hinterlands’

Micah Stanek, Lecturer

“[T]he grandeur of the place fell short of what one would suppose or expect from the conjunction of two such mighty rivers, draining so much of the world’s surface; but while, as they said, there was no high elevation from which one could view the approaching and uniting rivers, there was yet that strange but well-known feeling arising at the sight of the giant-like streams coming together and uniting their forces to march onward to the sea.”

—John M. Lansden paraphrasing Major Long’s 1819 description of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers Confluence in “A History of the City of Cairo Illinois” (2009, p. 40).

Fort Defiance—once a Union military camp, now an afterthought of a state park—defies nothing. The landscape is passive, rigid, and unremarkable. The green rectangle does not reveal or engage its significance as the confluence of two of North America’s most “mighty rivers.” This makes Fort Defiance State Park an ideal site for challenging landscape ideas such as the park, the memorial, the river economy, the political boundary, and the site itself. The studio situated this regional landscape in a global context to understand “site” as a confluence of global flows.

The Mississippi River is a system of confluences. From the headwaters in Minnesota, the river encounters and combines its 167-odd tributaries as it meanders 2320 miles to the Gulf of Mexico. The watershed spans from the Rockies to the Appalachian Mountains, connecting Three Forks, Mont. to Pittsburgh, Pa. Through portages and canals, humans have further connected the Mississippi River to the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean. The river system supported thousands of years of human settlement before it became strategic in the colonization of North America and essential in the establishment of early American settlements and trade patterns. Though railroads and highways superseded river trade in the 19th and 20th centuries, the river system still sees more than 500 million tons of shipped goods per year, connecting the Mississippi to the rest of the world.

“[C]ontexts imply other contexts, so that each context implies a global network of contexts.”

—Arjun Appadurai, “Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization” (2011, p. 187).

The mingling of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers at this site implies other confluences. Students were challenged to understand the site in terms of its nested hinterlands, studying ecological, cultural, and economic flows throughout the river system and over time. They also investigated the site in terms of global trends.

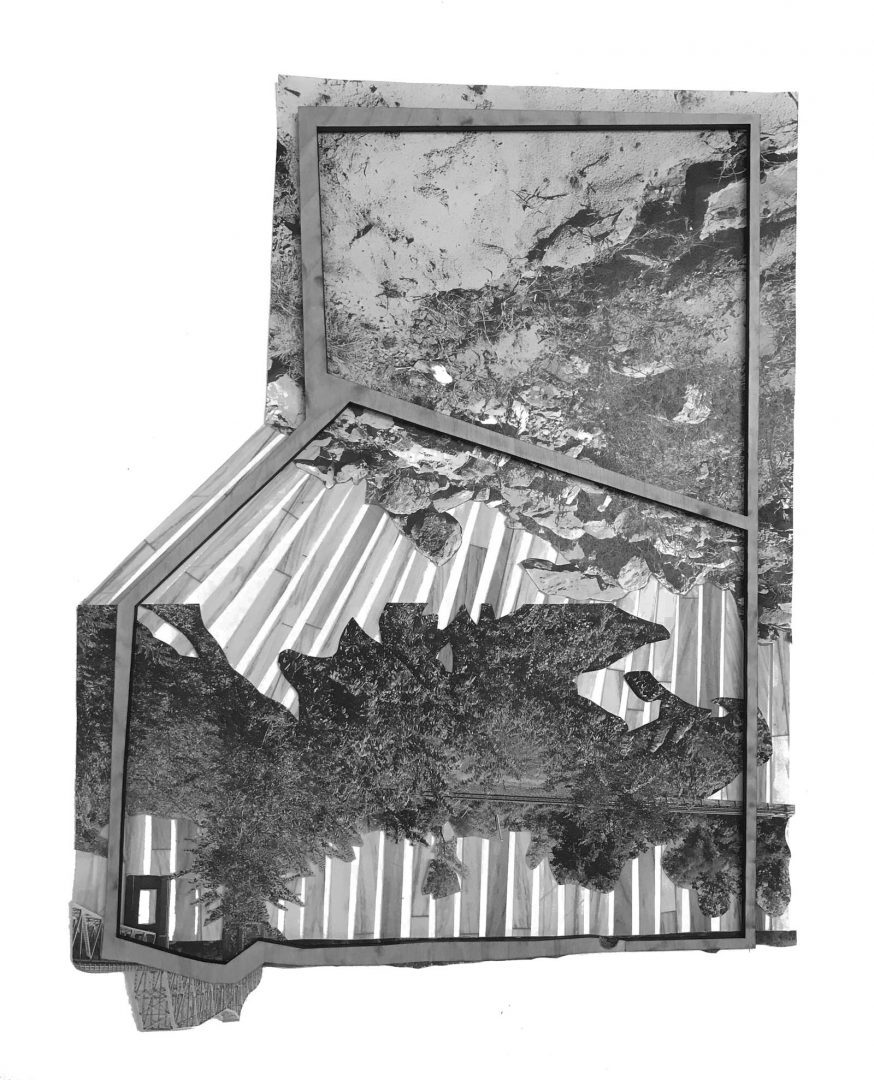

Traveling down river roads from Grafton, Ill. to New Orleans, students contemplated shifting patterns of migration, production, trade, and ideology along the river. Drift materials served as evidence of the hinterland, and found materials were used to study the production of space in an implicated landscape. Challenging the static, pastoral landscape, students projected futures for the state park that were productive, contingent, and perhaps even defiant.

Virginia Eckinger

Virginia Eckinger

Virginia Eckinger

Virginia Eckinger

Dongzhe Tao

Dongzhe Tao

Virginia Eckinger

Dongzhe Tao

Dongzhe Tao